We will read together, not alone

Reflections on the workshop Text and Contexts from the Decentered History of Women’s and Feminist Resistance

As part of the programme Archeology of Resistance: Corrective for the Future, curated for the 29th edition of the City of Women Festival by Iva Kovač, the participants of the workshop Text and Contexts from the Decentered History of Women’s and Feminist Resistance gathered at Ljubljana’s Škuc Gallery on 25 October 2023. The workshop dealing with intertextual and contextual reading was conducted by Jovana Mihajlović Trbovc. In an online talk with co-editor Zsófia Lóránd, she first presented the upcoming publication of the book Texts and Contexts from the History of Feminism and Women’s Rights: East Central Europe, Second Half of the Twentieth Century. The other two co-editors of what was an extensive project were Adela Hîncu and Katarzyna Stańczak-Wiślicz.

Together with collaborating experts, the researchers covered the entire area of East-Central Europe and gathered relevant sources dealing with local feminisms and women’s rights from the period after the Second World War up until the early 1990s. The content of the cataloguing project was not divided by country, but rather according to the prevalent themes. In doing so, the editors wanted to avoid the assumptions that some countries are more developed than others, instead drawing attention to the common demands of feminist movements everywhere. At the same time, they highlighted the similarities and dissimilarities of an extremely vast geographical area, which had been exposed to some of the prevailing currents of thought with varying degrees of intensity – not only the ideological tenets of political systems, but also the ideas of other contemporary world feminisms.

All the exceptionally diverse texts covered were translated anew from their original language, including those that had already been previously translated into English. The key and practical part of the workshop was thus based on presenting the methodological principles, on which every last individual contribution within the project is based. The original sources were all translated into English and accompanied with editorial notes. After reading the original working text and translation, the workshop participants began discussing the power and responsibility of an editor, whose guidance and contextualisation of facts can enable comprehension regardless of the reader’s previous knowledge. In some sources, like journalist pieces written for daily newspapers, certain facts, specific to the general knowledge of the time, are treated as self-evident but are little known to readers thirty years later. We were thus able to observe the bending of history and its contingency. The footnotes are actually a materialisation of the significance of a wholesome access to information and the importance of understanding the background and references within which any piece of writing is created. This is especially true for marginal and marginalised topics, including feminism and the women’s rights struggle, which are often historicised in ways that differ from the methods of regular history books. The marginalisation is all the more noticeable in any part of the world that is not Western Europe or North America and has thus far been studied in an individual, piecemeal way.

The translation accompanied by footnotes is followed by a section devoted to context, which deals with the text as a whole and situates it thematically into the place and time of its origin, including information on preceding events within a certain field as well as the potential implications of the piece of writing. The context also includes a bibliography, which makes it easy for any interested researcher to dig deeper. The author’s biography, including a bibliography and other important work, serves a similar purpose. As Mihajlović Trbovc pointed out during the workshop, their research was meant to be an entry point for further investigation, which is why it includes every possible reference that they were able to obtain. Its purpose is to spread knowledge and expand the collective understanding of the subject. The book that was presented at the workshop was created through the cooperation of many experts, while the research process took several years in the form of meetings and too many online conversations.

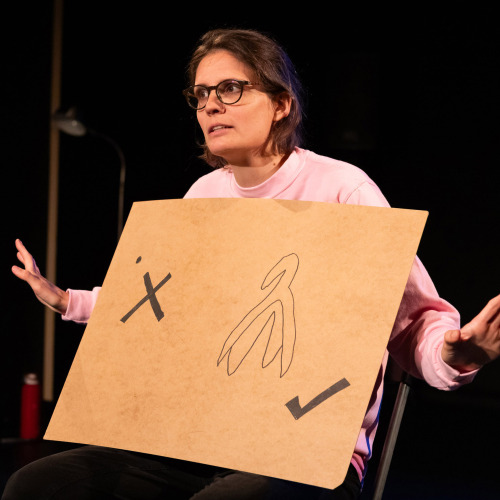

It was later presented again in a group setting for the interested public as part of the City of Women festival. The participants, seated on chairs temporarily forming a circle in the gallery space, had the possibility to contribute and understand the subject communally. This was a way to contrast the architecture of educational institutions, which uncompromisingly places the teacher’s desk in front of the gathered students. The traditional, ex cathedra way of imparting knowledge presupposes a consecrated knowledge bearer and is rooted in liturgical traditions. In spite of the (long since discovered, but still) alternative ways of active teaching and the recognised potential of concepts like the ignorant schoolmaster and the emancipated spectator,[1] the traditional way remains one of the first forms of receiving knowledge within educational institutions. Acquiring knowledge, expanding horizons, and changing habits as well as customary ways of thinking are supposed to be the basis of pedagogical processes that are far from over after exiting the educational system. As human beings, we are curious, evolving creatures, capable of learning throughout our lives. However, being in constant pursuit of the values of a neoliberal capitalist system, we are simply not encouraged to do so. An individual within this system ends up lonely and overworked due to the constant but never sufficient workload, while at the same time misled into believing that they are never good, smart, or capable enough – because in the tasks that would require cooperation, they are left to themselves, or else the community around them turns out to be nothing but a simulation. The time devoted to such supposedly unnecessary activities as engaged self-education thus becomes an important part of the contemporary question of class – who even has the time, in the context of a financial survival struggle from one precarious job to the next, to contemplate the development of one’s own thought, let alone to compare it to historical references or find its context within contemporary theoretical frameworks? Within a society that encourages an individualistic approach in far too many aspects of life, doing certain things together actually becomes a radical and rebellious act.

[1] The Ignorant Schoolmaster and The Emancipated Spectator are book titles of the French writer Jacques Rancière.